History of The Musical Stage

1980s III: Mega-Musicals & More

by John Kenrick

(Copyright 1996; revised 2014)

(The images below are thumbnails – click on them to see larger versions.)

Mega-Musicals: Britain's Revenge

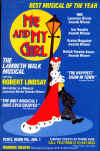

The

original flyer announcing the arrival of Me an My Girl

on Broadway in the summer of 1986.

The

original flyer announcing the arrival of Me an My Girl

on Broadway in the summer of 1986.

From the mid-1980s on, British musicals flew across the Atlantic season after season like an implacable invading force. The happiest of these imports was Me and My Girl (1986 - 1,420 performances) a heavily revised World War II London musical comedy hit with songs by Noel Gay. Shakespearean actor Robert Lindsay won a Tony for his ingratiating performance as poor cockney who inherits an Earl's title. American audiences embraced a show once dismissed as "too British" for Broadway.

The other "Brit hits" of this decade were all brand new. Relying on pop rhythms, stage hydraulics and high-tech special effects, these shows came to be known as mega-musicals. In these behemoths, substance took a backseat to spectacle, and occasional hints of humor were buried in oceans of soap opera sentiment. Although these tech-heavy presentations came with a high price tag, the best mega-musicals ran for decades, selling tickets to millions of people -- particularly tourists who had long since fallen out of the habit of going to the theatre.

Few noticed that these British and French mega-musicals were direct pop-flavored descendants of a form thought long-dead -- operetta. It was no accident that these shows almost always replaced their pop-voiced original casts with singers who had operatic credentials. No one else could deliver such sweeping melodies and gushing emotions eight times a week.

Andrew Lloyd Webber's Starlight Express was a tremendous hit in London (1984 - 3000+ performances), with hydraulic ramps that allowed roller-skating actors to careen through the Apollo Victoria Theatre. It fared less well on Broadway (1987 - 761 performances), where critics dismissed it as a minor children's show blown out of proportion. No one really cared who was in the cast. For the first time since the Hippodrome shows of the early 1900s, it was all about the spectacle. But Starlight Express did well on tour, enjoyed a long run in Las Vegas, and was revived with tremendous success in London.

The French team of Claude-Michel Schonberg & Alain Boubil first offered their musical version of Victor Hugo s epic novel Les Miserables as a recording, then as a Parisian stage spectacle, with a sung-through score that sounded like a pop version of grand opera. British producer Cameron Mackintosh became involved, teaming with the Royal Shakespeare Company and Cats director Trevor Nunn to revamp it into an international sensation. Mackintosh brought Les Miserables to the West End (1985 - London), Broadway (1987 NY - 6,680 performances), and most of the other cities in the civilized world. The English translation was no work of art, but the strong plot and hydraulic sets wowed most theatergoers. The logo, with little, bedraggled Cosette set against the French tri-color, became familiar on every imaginable sort of souvenir – including pricey re-prints of Hugo's novel.

Les Miserables was the first mega-musical with any dramatic merit. Audiences did not just marvel at the hydraulics -- they were moved by the sentimental story of thief-turned-saint Jean Valjean and the myriad of characters involved in his life. Dedicated fans and hoards of tourists kept Les Miz's turntable stages whirling well into the next century on both sides of the Atlantic. By 2014, Broadway had already seen two revivals.

Sondheim vrs. Webber: Round Two

The Broadway program cover to Lloyd Webber's

The Phantom of the Opera.

The Broadway program cover to Lloyd Webber's

The Phantom of the Opera.

The following season brought Andrew Lloyd Webber s The Phantom of the Opera (1988 - 11,000+ performances, still running), with the composer and Cameron Mackintosh co-producing. The lush score featured uninspired, babbling lyrics set to lush pop-operetta melodies, and an ending that departed completely from Gaston Leroux's classic novel. Harold Prince's lavish production made the show another triumph of form over function. Broadway audiences did not mind paying a record-setting $45 a ticket when they could see the money on stage in scene after lavish scene. Stellar performances by Michael Crawford and Sarah Brightman helped.

Most theatergoers augmented the show's income by taking Phantom mementos home with them. Phantom mugs, sweat shirts and masks (not to mention animated cymbal-crashing monkey music boxes) poured forth in a marketing blitz. Just as Cats had forced 42nd Street to evacuate the Winter Garden six years before, Phantom of the Opera now pushed 42nd Street out of the Majestic Theatre and across the street to The St. James. Literally and figuratively, the American musical was in a forced retreat. Producer Cameron Macintosh told one interviewer that Broadway was now "just another stop on the American tour." The British were not only back on top – they were downright cocky about it.

That same season, Stephen Sondheim and director-librettist James Lapine collaborated on Into The Woods (1987 - 769 performances), combining revised versions of several classic fairy tales to illustrate that nothing goes happily ever after, but also assuring audiences that "No one is alone." Although Phantom walked off with the Tony for Best Musical, Sondheim was able to relish that season's Tony for Best Score. But the overwhelming popularity of Lloyd Webber's show was undeniable, and both its London and New York productions remained sold out for more than two decades. Critics and scholars had no difficulty defining the difference between Lloyd Webber and Sondheim. For example --

"Lloyd Webber is unquestionably a skilled craftsman, manipulating theatre technique in precise, complex, extraordinary detail, but he has not shown much original creativity. He depends heavily on the tricks of composing, using the fundamental and simplistic ideas of each category . . . When Sondheim writes pastiche, he does so for dramatic effect. . . Andrew Lloyd Webber doesn't bother with dramatic justifications -- he quotes from a wide range of musical sources, often anachronistically. . . Sung-through shows lack the integration that makes the American musical the great and original art form it is."

- Denny Martin Flinn, Musical! A Grand Tour (New York: Shirmer Books, 1997), pp. 474-475.

From the Home Team

As the British stage invasion rolled on, American writers and producers were hard pressed for new ideas, but as the 1980s ended, two Broadway musicals broke through to popular success:

- Grand Hotel (1989 - 1,077 performances)

was a resurrected George Forrest & Robert Wright

project that had closed on the road in 1958. Based on the classic novel, play and MGM

film, it told of the intertwined fates of guests at a posh Berlin hotel in

the early 1930s. To the dismay of the original composers,

director Tommy Tune called in Nine's

Maury Yeston to replace about half of the

score. The revised show got mixed reviews, but a combination of limited

competition, good word of mouth and strong marketing kept the show running for several years. Big-name

cast replacements – including screen dance legend

Cyd Charisse – helped make Grand Hotel

the first American musical since La Cage Aux Folles to top 1,000 performances on Broadway.

- City of Angels (1989 - 878 performances) won the

1989 Tony for Best Musical thanks to an occasionally hilarious Larry Gelbart

libretto about a screenwriter

interacting with the fictional characters in his latest script. The

Cy Coleman-David Zippel score

was pleasant, but some of the songs echoed numbers from previous Coleman shows

-- and the tech-heavy production (including computer animation sequences) left

little room for profit.

By the time all three of these American hits had come and gone, the mega-musicals Les Miserables and Phantom of the Opera were still playing to capacity, with multiple companies packing them in worldwide. So the 1980s were very much the decade when the Brits got a little of their own back. Americans would soon outdo the British mega-musical at its own game – but a cure can be worse than the sickness.