Dance in Screen Musicals

by John Kenrick

Copyright 2004

- Early Clodhopping

- The Revolution: Berkeley

- Dance as Romance: Astaire

- Many Élan: Kelly

- Broadway's Borrowed Magic

- Dancing or Editing?

Early Clodhopping

Charles King and his

clod-hopping chorines appear on this page from the souvenir program for

Broadway Melody (1929).

Charles King and his

clod-hopping chorines appear on this page from the souvenir program for

Broadway Melody (1929).

From the time Thomas Edison invented moving pictures, film was used to capture theatrical dancers at work. Early silent clips include cake walking minstrels and vaudeville "skirt dancers," as well as partial performances by such classical dancers as Anna Pavlova and Isadora Duncan. Dance played a role in the golden age of silent film, most notably when Rudolph Valentino ignited a world-wide tango craze in the 1920s.

By 1929, sound completely supplanted silent film in Hollywood, and cinematic professionalism was temporarily replaced by a spirit of desperate improvisation. It was easy for inexperienced men with self-confidence to talk their way into top production jobs. Cameras were encased in immobile noise-muffling booths, giving early talkies a static appearance. As a result, most musicals filmed between 1928 and 1930 are hard to watch today, even for their camp value.

The earliest Hollywood musicals include some gifted performers and more than a few memorable songs, but their dance sequences are almost always ghastly. Consider Broadway Melody (MGM - 1929), the first musical to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. When leading man Charles King sings the title tune in the film's climactic stage revue, he is accompanied by a line of chubby, clodhopping chorus girls, one of whom enlivens the number by tapping "en point" in ballet toe shoes.

That same year, Broadway favorite Marilyn Miller starred in a screen version of her long-running stage hit Sally (National - 1929). While Miller's acting and singing are unimpressive, her dance sequence during "Wild, Wild Rose" explodes with energy and tangible star quality. Poor camera angles notwithstanding, she sparkles, making this the first hint that dance could add as much life to musical film as it did to stage shows. Sadly, Miller made few films, and dance remained an afterthought in screen musicals for several years more.

The Revolution: Busby Berkeley

Warner Brothers' stellar cast

is featured on the original sheet music cover for "You're Getting to Be a

Habit With Me" from 42nd Street (1933). This backstage saga rekindled

America's interest in musical films.

Warner Brothers' stellar cast

is featured on the original sheet music cover for "You're Getting to Be a

Habit With Me" from 42nd Street (1933). This backstage saga rekindled

America's interest in musical films.

Busby Berkeley built a reputation as dance director for several Broadway shows, and staged forgettable numbers for several films starring Eddie Cantor. But Berkeley reshaped his career and the future of musical film when he created the dance sequences for Warner Brothers' backstage saga Forty-Second Street (Warner Bros. - 1933). Berkeley became the first filmmaker to realize that screen choreography involved the placement and movement of the camera as well as the dancers. Instead of filming numbers from fixed angles, he set his cameras into motion on custom built booms and monorails. Berkeley's trademark was to put dancers in kaleidoscopic formations and film them from overhead – if necessary, cutting right through the roof of a soundstage to get the right shot. Sweeping views of geometrically arranged dancers moving in unison delighted a nation desperate for cinematic distraction from the Great Depression Sometimes erotic, sometimes vulgar, often spectacular -- the best of Berkeley's images still dazzle viewers today.

Dance as Romance: Fred Astaire

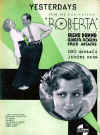

Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire

share the original sheet music cover for Robertas' (1935) hit song

"Yesterdays" with co-star Irene Dunne.

Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire

share the original sheet music cover for Robertas' (1935) hit song

"Yesterdays" with co-star Irene Dunne.

Broadway veterans Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers made little headway in Hollywood until RKO Studios cast them as supporting players in Flying Down To Rio (1933). When they touched foreheads and danced a few steps in "The Carioca," their energy turned the number into the highlight of the film. The film had a surprising impact on viewers. Future director Stanley Donen described his reaction this way --

I was nine, and I'd never seen anything like it in my life. I'm not sure I have since. It was as if something had exploded inside me. . . I was mesmerized. I could not stop watching Fred Astaire dance. I went back to the theatre every day while the picture was playing. I must've seen it at least twenty times. Fred Astaire was so graceful. It was as if her were connected to the music. He led it and he interpreted it, and he made it look so effortless. He performed as though he were absolutely without gravity.

- as quoted by Stephen M. Silverman in Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and His Movies. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), pp. 11-13.

Producer Pandro S. Berman saw the possibilities, and persuaded the studio to design a star vehicle for Astaire and Rogers. In The Gay Divorcee (1934), they danced and romanced, inventing what became a set formula – a devil-may-care playboy and a sweet girl with spunk get into a tangle of mistaken identities, fall in love on the dance floor (to something like Cole Porter’s "Night and Day"), eventually resolve their misunderstandings and foxtrot happily ever after. Despite glamorous surroundings and witty banter, Astaire and Rogers are clearly likeable folks "just like us" – or just like most people wished they could be.

A popular cliché (suppossedly coined by Katherine Hepburn) suggests that "Fred gave Ginger class, while she gave him sex." While there may be some truth in this, the fact is that both Astaire and Rogers already had each of those qualities. It was the indefinable connection between their screen personas that made their class and sex appeal apparent and irresistible. Their films were major moneymakers. Choreographed primarily by Astaire and his associate Hermes Pan, these were the first musicals (on stage or screen) to make substantial use of dance to develop plot and character. The scores were provided by some of the greatest composers in the business, but the audience was primarily interested in Astaire and Rogers.

Manly Élan: Gene Kelly

Broadway hoofer Gene Kelly made his musical screen debut co-starring with Judy Garland in For Me And My Gal (1942). Kelly's good looks and macho dance style made him an immediate audience favorite, but his career really took off when he was loaned out to Columbia for the surprise hit Cover Girl (1944). Assistant choreographer Stanley Donen put Kelly in a series of winning dance numbers, most notably an "alter ego" dance duet with his own reflection. Kelly won such acclaim that MGM refused to loan him out for any future musicals, and the studio began to treat him like a major star. Kelly helped pop crooner Frank Sinatra look like a capable hoofer in Anchors Aweigh (1945), and shared a dazzling song and dance duet with Fred Astaire in Ziegfeld Follies (1946).

Kelly then starred in and choreographed the screen version of On The Town (1949), the first of several films he would co-direct with Donen – a former Broadway chorus dancer with a remarkable instinct for musical film. Donen, Kelly and producer Arthur Freed would collaborate on some of the finest screen musicals ever made. Kelly understood what a remarkable team the Freed unit was.

"The members of the group who worked at MGM during my tenure there were very serious about musicals. That is not to say we didn't make them to entertain and lift the spirit, but we thought that to do this effectively they had to be superbly crafted; and that meant the closest kind of collaboration among the choreographers, directors, producers, musicians, conductors, musical arrangers, designers, costumers – the list is endless. There were probably more assembled talents in this field at Metro than anywhere else at any other time."

- Kelly's introduction to Clive Hirschorn's The Hollywood Musical (NY: Crown Publishing, 1981), p. 7

Even as the old studio system self-destructed in the 1950s, Kelly brought screen dance to new levels of sophistication.

Borrowed Magic: Broadway on Screen

From the 1950s onwards, most of the important Hollywood musicals were screen adaptations of Broadway shows. In many cases, Broadway choreographers were given the opportunity of recreating their stage dances for the big screen. As a result, we have beautifully filmed versions of Agnes DeMille's ballets in Oklahoma and Carousel, Jerome Robbins' dances in The King and I and West Side Story, and Bob Fosse's work in Damn Yankees and The Pajama Game.

In the 1960s, dance became an increasingly minor element in the ever-decreasing number of screen musicals. There were exceptions, most notably Marc Breaux and Dee Dee Wood's inventive ensembles in Mary Poppins (1964) and Fosse's dances in Sweet Charity (1969). Broadway choreographer Onna White preserved the best of her stage dances in the screen version of The Music Man (1962), and created some extraordinary new ensembles for the Academy Award winning Oliver (1969). The few successful film musicals of the 1970s had little in the way of dance. Grease (1978) broke box office records, but Patricia Birch's period spoofs did not rate as anyone's idea of inventive choreography.

The 1980s and 90s saw only a handful of live action musical films, none with noteworthy dances. After little more than half a century, screen musicals were dismissed as the province of animated beauties, beasts and candlesticks.

Dancing or Editing?

With the rise of cable television in the late 20th Century, the MTV channel found a massive audience showcasing music videos by rock and pop stars. Fast, inventive editing and lots of electronic razzle dazzle made the most of the sometimes limited dancing talents of the performers. As the 21st Century dawned, live action screen musicals like Loves Labour's Lost (2000) and Moulin Rouge (2001) used such MTV-inspired techniques to make their non-singing, non-dancing stars look and sound like musical pros. The results were, at best, uneven.

When Chicago (2002) became the first screen musical to win the Academy Award for Best film in 35 years, young fans were delighted. But those who remembered the extended takes that let one relish the bona fide dancing talents of Astaire, Kelly and Powell could not help noticing that every dance sequence in Chicago involved dozens (if not hundreds) of quick edits. There were many Broadway veterans in the ensemble numbers, but it was hard to distinguish them from the first time dancers. So although Rob Marshall's choreography looked great, some wondered if it was a triumph of great dancing or clever editing?